Choosing the Right Ultrasound Transducer: A Guide for Vets

- Echo Vet Solutions

- Jan 1

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 4

This article is part of a three‑part blog series on veterinary ultrasound CPD. The series is designed to help vets understand the fundamentals of ultrasound physics, recognise common artefacts, and apply these skills confidently in clinical practice.

Part 1: Choosing the Right Ultrasound Transducer

Part 2: Understanding Ultrasound Artefacts in Veterinary Medicine

Part 3: From Physics to Practice – Applying Ultrasound Skills in Veterinary Clinics

Introduction

Ultrasound is one of the most versatile diagnostic tools in veterinary medicine. From routine abdominal scans to advanced echocardiography, vets rely on ultrasound to make fast, accurate decisions. But the quality of those decisions depends on one crucial factor: the transducer. Choosing the right probe and understanding how it works is the foundation of successful imaging. The ultrasound transducer choice directly affects image quality, diagnostic accuracy, and scanning efficiency. In this guide, we’ll explore how vets can select the most appropriate transducer for abdominal, cardiac, and musculoskeletal applications — with practical tips for probe types, frequency, and patient size.

You’ll often hear people use the words “probe” and “transducer” when talking about ultrasound. In practice, they mean the same thing, the handheld device you use to scan. “Transducer” is the more technical term, while “probe” is the everyday word most vets use. For our purposes, we’ll use them interchangeably.

How Transducers Work

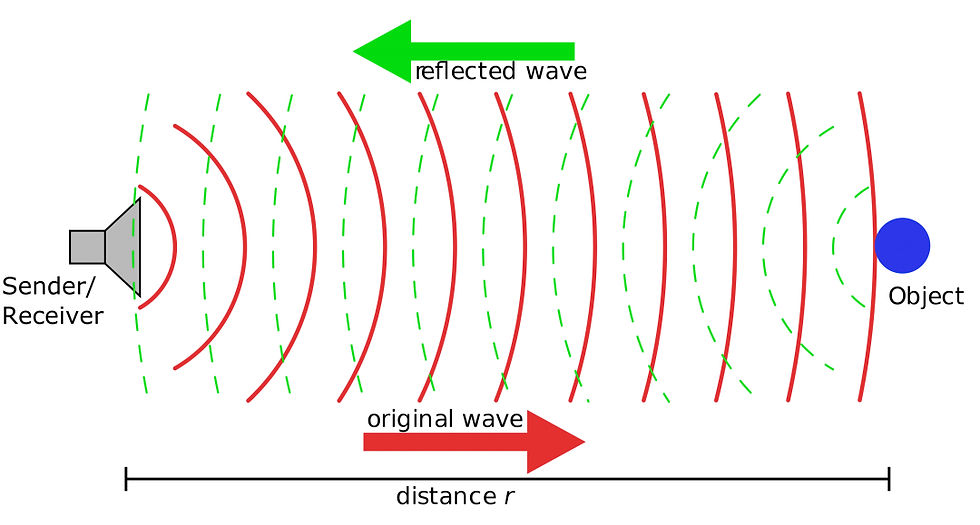

At the heart of every ultrasound probe are piezoelectric crystals. These crystals convert electrical energy into sound waves, which travel into the patient’s body. When the waves encounter tissues of different densities, they bounce back as echoes. The machine processes these echoes into the grayscale images you see on screen.

This process is universal across all ultrasound machines, whether you’re using a portable point-of-care device or a high-end echocardiography system.

Image credit: Georg Wiora (Dr. Schorsch), “Sonar Principle EN”, CC BY‑SA 3.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Probe Types and Their Uses

Linear probes – High-resolution images of superficial structures. Ideal for tendons, small patients, and superficial abdominal organs.

Curvilinear (convex) probes – Wider field of view, commonly used for abdominal imaging in small animals.

Phased array probes – Designed for imaging between ribs and deeper thoracic structures. Essential for echocardiography.

Phased array probes are typically favoured for cardiac imaging, whereas micro-convex probes are especially useful for abdominal scans and smaller patients. Nonetheless, specialised and costly cardiac probes or scanners are not necessary in general practice. With the right technique, a standard abdominal probe can effectively be used for accurate diagnosis and staging of common cardiac diseases such as degenerative mitral valve disease (DMVD) in dogs. In our training sessions, we will show you precisely how to maximize the use of the equipment you currently possess.

Frequency Trade-Off

High frequency (7–20 MHz): Excellent resolution but limited penetration.

Low frequency (2–5 MHz): Greater depth but reduced detail.

Choosing the right frequency depends on the patient’s size and the organ of interest.

Begin by using the highest frequency that still provides adequate penetration for the specific anatomy, this maximises image clarity without compromising depth.

Optimising Image Quality

Probe choice is only part of the equation. Adjusting gain, depth, and focal zones can dramatically improve image clarity. These settings allow you to tailor the image to the patient and the clinical question.

Our in‑practice ultrasound CPD courses are designed to give you hands‑on confidence with your own equipment. You’ll learn how to select the right probe, adjust machine settings effectively, and navigate controls with ease. We cover the core principles of ultrasound, from patient preparation and probe types to image acquisition. You’ll also develop the skills to recognise artefacts and interpret images accurately. By training in your own clinic, you’ll build practical expertise that translates directly into better patient care.